Hi there! Today I’ll be talking about why we split our data into training, validation and test sets and gradient descent.

I’ll also teach you a quick and dirty trick to speed up your processing tasks a thousand fold… in the Linux shell, of course!

This is part 2 of a six part series. You can find part 1 here!

Training, Validation and Testing sets

OK, so last time we got a bunch of hotdog and nothotdog images (actually, image urls), but what do we do with them??? We are going to feed them to a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). We’ll talk more about that soon enough, but now I’m going to explain why we need to split our images.

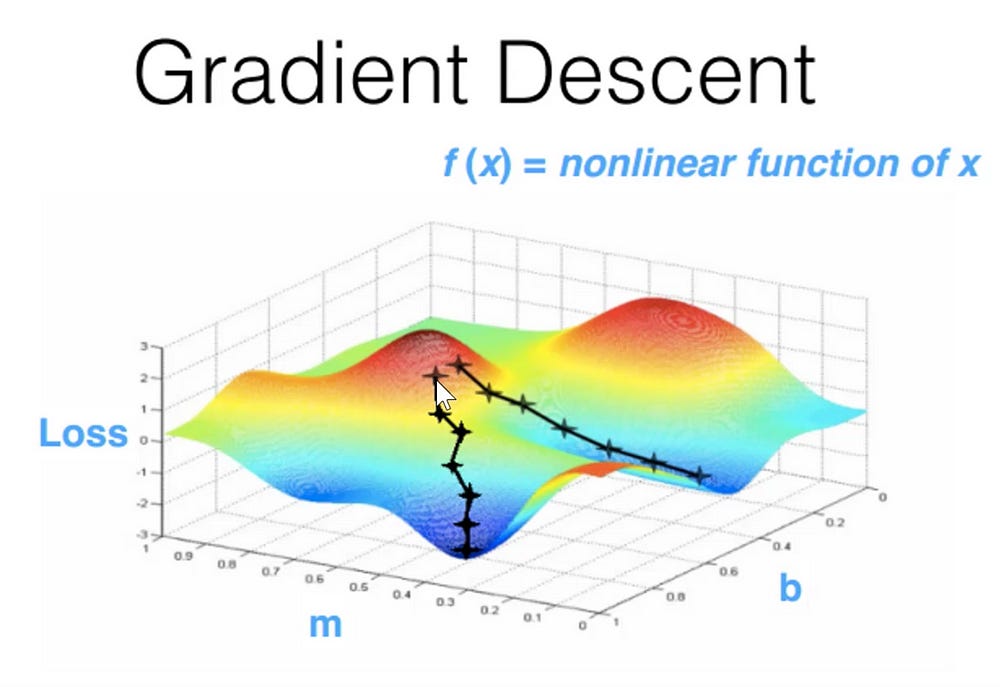

Without even understanding what a CNN is, we can understand the process of training one. It’s basically the same as with any Machine Learning model. We will initialize the model parameters randomly. With each iteration of training, we will make predictions about the images in our training set: are they hotdogs? are they not? We will score our predictions to see how badly we are doing: that is what’s known as the loss, and a loss function is just a function that tells us how far we are from perfect predictions. After that, we will tweak our model parameters in order to slightly improve our loss. For that we need to know in what direction to tweak them, and that is why our loss function must be differentiable with respect to the model parameters. We will iterate once and again, slowly going down the “energy landscape” defined by our loss function. That’s what’s known as ‘gradient descent’. It’s actually not the only way to minimize a function, but it’s a vivid enough mental image that it’s what we teach.

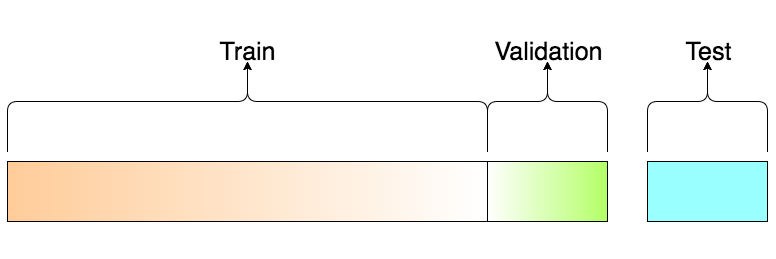

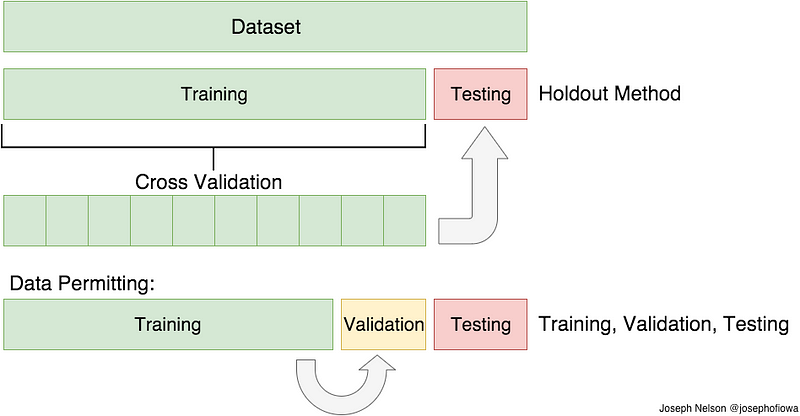

So, what about these sets? We use the training set to estimate our parameters. But these parameters are those that optimize the loss function for the samples in the training set. To get an idea of how well the model will perform in unseen samples, we will calculate the value of the loss function on the validation dataset. Once we get a noticeable higher loss on the validation set than the training set, we know we have overfit: our model parameters are too specific to the training set to be of use.

What about the test set, then?? Well, we are not going to be training one model. We will train a lot, changing the configuration of the network, how long we train, and many other variables that describe the learning process. Those are called hyperparameters. Once we finish our training and get the validation loss as low as can be, will it be a good estimate of the loss in unseen samples? No, because we will have optimized the hyperparameters for that particular validation set!! That’s what we use the test set for. It will be a number of samples we leave out until after we have finished training, and its only use is to get an estimate of the loss function in unseen samples.

Is everything clear? Then let’s get to it!

Getting the images and splitting them

The actual splitting is pretty quick and easy to do with bash. We could also do it with Python, of course, and I will probably write a blog post on how to do it at some point, but it’s quicker to do it with bash and I’m just itching to start playing with DL, aren’t you?? These preliminaries have been long enough already.

First, we need to download them. We will use the wget Unix command. We need to set a timeout, because some of the domains don’t even exist anymore and we don’t want to hang up waiting for them to respond.

Also, we will use a little trick to download all the images in parallel. Instead of waiting for each request to complete, we can use the & operator in bash to spawn a background process for each request. That will set all the requests and process them in parallel. Instant parallel processing FTW! We are going to have to make the requests wait a bit though, or we’ll overwhelm the system. We do that with sleep.

%%capture

%%bash

# The capture cell magic suppreses output so we aren't flooded by warning messages.

# Remove it if you want to inspect them.

# The bash cell magic allows us to use bash inside a jupyter notebook.

# Much like !, but for a whole cell.

mkdir -p data/train/hotdog/

mkdir -p data/train/nohotdog/

cd data/train/hotdog/

# Download every url from the hotdogs file

# Wait 20s for each image

for l in $(cat ../../../hotdogs_sample.txt)

do

# Download with wget, the & at the end makes each command run in parallel

wget --timeout 20 --dns-timeout 20 $l &

# Wait .5 seconds before proceeding to the next turn of the loop

sleep .5

done

cd ../nohotdog/

# Download every url from the nohotdogs file

# Wait 20s for each image

for l in $(cat ../../../nohotdogs_sample.txt)

do

# Download with wget, the & at the end makes each command run in parallel

wget --timeout 20 --dns-timeout 20 $l &

# Wait .5 seconds before proceeding to the next turn of the loop

sleep .5

done

OK, now we have all the available images from each list in a data/train/$CLASS folder. At this point, we are regretably going to have to do some manual processing. Some of the image urls lead to a “not available” webpage and make us download a non-image file. Some others lead us to download a stock “file not found” image. We also get a lot of wget-log.nnn if we run the code from a terminal. Still others don’t have a .png or .jpg ending, but are images anyway.

Ideally we would handle all these issues in code. We won’t be doing that here because it would lead me to explain a bunch of concepts that are not related to DL at all, and because I firmly believe in getting results as quickly as possible with the simplest possible tools. Only once you have a POC, or MVP, or however you want to call it, then it’s the time to start productionizing and improving it. For this tutorial, the straight line to getting results implies going over the images manually and removing the invalid ones. That took me about 3 minutes for the hotdogs, and around 15 minutes for the other images (that was boring). Totally not worth the automation effort if we are doing it only once.

Anyway! We finally have all the images we need! More than we strictly need, actually:

%%bash

ls data/train/hotdog/ | wc -l

ls data/train/nohotdog/ | wc -l

870

5870

They are in a single directory. The only thing we need now is to split them intro training, validation and testing sets. Since our classes are unbalanced, we’ll better be careful to take a similar proportion of each: around 7 not hotdogs for every hotdog.

import os

hotdogs = len(os.listdir('data/train/hotdog/'))

nohotdogs = len(os.listdir('data/train/nohotdog/'))

hotdogs, nohotdogs, nohotdogs/hotdogs

(870, 5870, 6.747126436781609)

Let’s do the split, once again quick and dirty.

The directory structure we need to create is like this:

- data

- train

- hotdog

- nohotdog

- validation

- hotdog

- nohotdog

- test

- hotdog

- nohotdog

The reason that we need this particular directory structure is the tool we will be using, Keras. More information on future episodes!

For choosing the images we will use a very handy tool: sort -R (for random). that will allow us to do it fast and easy from the command line.

%%capture

%%bash

folders="data/validation/hotdog/ data/validation/nohotdog/ data/test/hotdog/ data/test/nohotdog"

for f in $folders

do

mkdir -p $f

done

for f in $(ls data/train/hotdog/ | sort -R | head -n 120);

do

mv "data/train/hotdog/$f" "data/validation/hotdog/"

done

for f in $(ls data/train/hotdog/ | sort -R | head -n 120);

do

mv "data/train/hotdog/$f" "data/test/hotdog/"

done

for f in $(ls data/train/nohotdog/ | sort -R | head -n 800);

do

mv "data/train/nohotdog/$f" "data/validation/nohotdog/"

done

%%bash

for f in $(ls data/train/nohotdog/ | sort -R | tail -n 800);

do

mv "data/train/nohotdog/$f" "data/test/nohotdog/"

done

And this way, we have separated the images into the three sets that we will need in order to train our model. Next time we will finally be able to play around with Deep Neural Networks!!

For me, this post also illustrates that having as many tools in your toolbox as possible (in this case I’m referring to shell scripting in addition to Python) is totally worth it. Were I to actually take this to production, it would probably be worth it to spend the effort require to translate this into Python to make it less brittle. However, being able to write a quick and dirty prototype to test the idea has allowed me to explore many more promising avenues than I could have otherwise.

What’s your experience? Do you have an opinion regarding Q&D prototypes?